What is dreaming but philosophy. What is philosophy but dreaming. Carl Jung was big on dreams. The basic idea behind Jungian dream theory is that dreams reveal more than they conceal. They are a natural expression of our imagination and use the most straightforward language at our disposal. In his philosophy behind dreaming he also rejected Freud’s theory of dream interpretation that dreams are designed to be secretive.

Photo by Robert Collins on Unsplash

One such dreamer who used his imagination to design the future of humanity was Shimon Peres. Peres was Israel’s ninth President, a three-time Prime Minister, a Nobel Peace Prize Laureate, loved and respected around the world. He considered himself both a dreamer and humanitarian more than he did a politician.

In 1994 he received the Nobel Peace Prize for orchestrating the Oslo Accords peace talks with the Palestinian leadership. Later, in 1996, he founded the Peres Center for Peace, whose aim was of “promoting lasting peace and advancement in the Middle East” by fostering tolerance, economic and technological development, as well as cooperation and well-being.

He became one of the greatest ambassadors for peace in our lifetime.

But if you had asked Mr. Peres what he did for a living, he would tell you he was a professional dreamer.

He would say, “Don’t use your brain to remember the past, use your brain to imagine and create the future.”

When I studied what made Disruptors more exceptional than others in the pursuit of their ideas, a common thread was their ability to dream on a grand scale. Not just as an extracurricular activity to enhance innovation, but as a completely radical way to shape the world. Their thinking and conceptual ideas were abstract in their origination, allowing them the same process as an abstract artist, seeing the same world we all see, just differently.

Disruptive thinking is symbiotic. It’s mycelial. It’s universal. It’s an alchemic formula that is part intuitive, part creative, part imaginative, always divergent, and it fosters playfulness, finding one’s unique vision, curiosity, and wonderment. And it requires one to be explorative and adventurous.

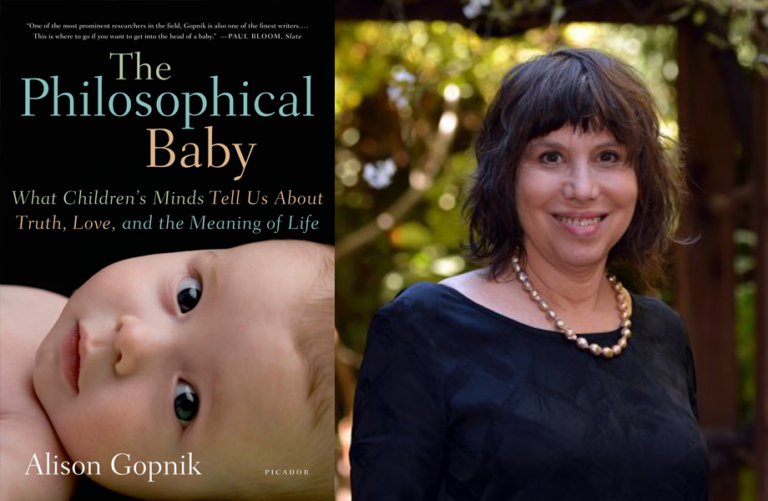

In her book The Philosophical Baby, Professor Alison Gopnik talks about the contrast between spotlight consciousness of adults and lantern consciousness of children. Her idea is about how we view the world, how we process this information, and how we develop our perceptions and understanding.

The reason children are so much better equipped to dream and think expansively is that they look at the world through this lantern consciousness. They take in everything, rarely missing anything, because it’s all so new, so different, so interesting. Everything is a discovery, a thing to be examined, or a puzzle to be explored, and, in the beginning, everything is an experiment: “What happens of you do this…?”

I like what Monty Don, a British horticulturist says that “As adults, compared to children, we close everything down based upon experience. We shutter out all the possibilities that are less likely.”

I took this to mean that we inhibit ourselves from traversing down a road that could seem more silly, bizarre, unusual, or to have unlikely consequences without even considering all the possibilities, simply for the fact that we already have a predisposed idea of what to expect. I refer to this as the flat world belief syndrome, not even willing to dream or entertain alternate possibilities.

Neuroscience is called predictive coding. Predictive coding (also known as predictive processing) is a theory of brain function in which the brain is constantly generating and updating a mental model of the environment. The model is used to generate predictions based upon perceived sensory input that are compared to actual sensory input. It’s kind of why we keep from freaking out when something doesn’t go as planned, as we strive to predict what we are seeing then attempt to course-correct for any errors.

Children, on the other hand, don’t think in terms of predictions, and therefore, initially, don’t draw conclusions. Their lantern consciousness, their divergent mindset, remains open to any and every possibility. This promotes imagination through an undefined reality.

In his book, The Doors of Perception, Aldous Huxley says that predictive processing is a measly trickle to the possibilities of what is out there.

“To make biological survival possible, Mind at Large has to be funneled through the reducing valve of the brain and nervous system. What comes out at the other end is a measly trickle of the kind of consciousness which will help us to stay alive on the surface of this particular planet.”

He further goes on to say that in the Western world, visionaries and mystics are a good deal less common than they used to be.

The sad part of experiments like these is that they discourage the sense of wonderment and excitement children feel, replacing it with the expectation of apprehension and disappointment.

This type of conditioning forces children out of their naturally intuitive thinking, and instead they ultimately will defer to a more pragmatic and rational mindset. The first is filled with wonderment and the joy of new experiences. The second offers the conditioning to look for the least likely outcome and prepare to pivot from the obvious. In this way, surprise, the willingness to be open to new challenges, and the ability to enhance one’s divergent thinking are stifled.

Soon, the child expects to be fooled or disappointed. One could argue that additionally, it challenges the child to think more rationally and cautiously, which is necessary to the framework of fitting into societal standards. They are conditioned to forgo surprise and wonderment for careful observation and analysis. Unfortunately, this conditioning diminishes their ability to foster and nurture the gifts that curiosity and wonderment can so eloquently provide.

By replacing one’s natural intuitive ability with rational logic, they become accustomed to hesitate and second-guess their observations. Intuitive thinkers, however, remain non-conclusive in their expectations and their sense of wonderment and curiosity allowing them to cultivate an adventurous nature. In this way, we can see that it’s still the more creative fields of endeavor that encourage this open-minded thinking style.

The ability to imagine and dream, when nurtured, allows for more roads to be travelled upon. Another way to look at this is to consider that rational thinking is a linear process, while, according to philosophers like Leonardo da Vinci and Antoni Gaudi, nature has no straight lines, and therefore, neither does divergent, intuitive thought.

Both intuitive and rational thinking have their place. Yet when we don’t teach, inspire, and promote one’s natural intuitive abilities, it constricts their thinking and willingness to challenge themselves.

I cannot state this more simplistically or elegantly than Professor Albert Einstein has done:

“The intuitive mind is a sacred gift and the rational mind is a faithful servant.

We have created a society that honors the servant and has forgotten the gift.”

One of the motivations for parents to promote rational thinking so early in childhood development is for the most obvious reason that children are likened to fully charged batteries. They are always on, bouncing around from thing to thing, whatever catches their attention in the moment. This can be frustrating, exhausting, and goes against the grain of order and rationality, so a parent can get frustrated by this seemingly wild, uncontrolled behavior.

Alison Gopnik says something interesting about a child’s perception, especially in the area of ‘paying attention.’

“We often say that young children are bad at paying attention. But what we really mean is that they’re bad at not paying attention, that they don’t screen out the world as grown-ups do. Children learn as much as they can about the world around them, even if it means that they get distracted by the distant airplane in the sky or the speck of paper on the floor when you’re trying to get them out the door to preschool.

So if you want to expand your consciousness, you can try psychedelic drugs, mysticism or meditation. Or, you can just go for a walk with a 4-year-old.”

There’s a phrase that British people tend to use, one that I learned from the Roald Dahl book, Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, it’s the word ‘gobsmacked.’ A ‘gob’ is slang for mouth. A gobstopper is the everlasting candy Wonka created. But to me, it has another connotation. Gobsmacked is one’s ability to be awe-struck, surprised, amazed. It’s a quality that children exude because they naturally don’t draw conclusions for the very reason that they want to remain surprised. And I know that adults can at times get gobsmacked because the road of logic they were traversing down didn’t yield the expected results, which surprised them.

So why is it then that dreaming is such an essential attribute to cultivate? When you dream, during sleep, parts of your brain shut down. This allows your mind to wander and it’s the reason so many odd things can get thrown together into the mix during a dreaming event, flying animals, suddenly being in a location and not knowing how you arrived there, falling or flying, seeing snakes or flowers growing out of solid rock… It’s permission to let your imagination run wild.

This same type of mind-wandering can take place when daydreaming. It involves fantasizing, pretending, and contemplating imaginary things behaving uncharacteristically like the buildings folding over onto themselves as in the movie “Inception.”

It’s an important tool when expanding one’s ability to think bigger. To dream is to create. To create is to explore. To explore is to develop and evolve.

This is the realm of artists, designers, builders, philosophers, writers, and in some cases architects. Societally we encourage these areas of creativity mostly when they show to be of usefulness or monetary value. But we don’t encourage, nor do we promote one’s creative abilities beyond a certain level, initially, because we haven’t seen any value in doing so. Creative pursuits are not grounded in security, a sound occupation, or a reasonable objective. Therefore, we tend to deem them as nothing more than fanciful, extracurricular endeavors.

Yet when some radical, free thinker develops something remarkable, we applaud their achievements. When an athlete goes beyond the norm of athletic ability and outperforms his opponents, when a composer or artist displays an amazing capacity to conjure something extraordinary, we applaud and marvel at their unique gifts and talents. And we even look to see if we too can replicate their successes. But we still don’t promote or encourage this thinking beyond a certain level of expectation.

The funny thing is that these dreamers, these idealists, these creators, are the ones who end up advancing our growth and evolution.

If you think about it, gasoline didn’t have a purpose initially, neither did electromagnetism, frequency-hopping, the pursuit of flying, rocketry, space travel, the science of radium, the development of computers, or the idea of cell phones, etc. Initially, they were all nothing more than someone’s fanciful idea, pursuit, or dream.

But once these lofty ideas were adopted into societal practices, we immediately saw their importance, merit, and value. And most of these are still around today and still extremely valuable.

Dreaming is exactly how we develop and go to the next level. So why aren’t we encouraging and requiring it on a larger scale?

Dreamers like Pythagoras, Copernicus, da Vinci, Galileo, Curie, Faraday, Farnsworth, Einstein, Parsons, Geary, Jobs, Musk, Bezos, and others, all initially got derisiveness, pushback and discouragement, yet all of their ideas became so vital to our development and evolution that we should be teaching and encouraging these habits of thinking and behavior to everyone.

Because we are a society that chases and reveres money, we don’t put value into these pursuits until they are likely to yield a reward. The Disruptors who dreamed big, initially didn’t even know if their dreams, their pursuits, their strange ideas would lead anywhere. Some even died broke. But none of them gave up. It was a part of who they were, and we are all the richer for it.

We should not forgo the benefits of rational thinking. It has an important place in areas like science, math, engineering, laws, civil practices, and values. But more importantly, we should not diminish, nor place the value and importance of intuitive thinking in second place, as this is initially where our biggest, boldest, and brightest ideas come from.

We need Disruptors to shake us up every now and then. The philosophy behind dreaming is that we need their unique visionary concepts to show us a new direction, to push our growth and evolution, to inspire us out of our complacency, to teach us how to reach higher, go farther, to dream bigger.

And it should be mandatory that we all learn this style of thinking, that we encourage and promote it within our children and not constrict or stifle their natural inclination towards being a visionary.

It is never too late for any of us to learn to regain these precious gifts of dreaming, intuition, and divergent thinking. Our future depends on it. And our need for creative pursuits demands we remain open to any and every possibility.

Typically, at this stage I offer a set of tools or tips to get you into the right frame of mind. But I think what Alison Gopnik said is so beautiful; “Go for a walk with a four-year-old.” And if you don’t have children then I suggest developing two essential tools of the dreamer: wonderment and curiosity.

Wonderment is simple; don’t approach anything with a predisposed idea of how it might turn out. Keep an open mind and embrace the experience. Adults will typically attempt to figure out how a magic trick is done so they can logically comprehend and reason its process. Children just enjoy the performance.

As for curiosity, again this is simple to develop. Don’t predispose your thoughts and instead ask questions that take you deeper. Attorneys will often ask questions they already know the answer to. And businesspeople ask questions that logically help them confirm and comprehend what is required of them.

What you want to do is to develop your learning and understanding of things in a way that offers an even broader perspective than ever before. As a parent, have you ever been annoyed or frustrated because your child asks question after question after question? Well, that’s how they learn, develop, and understand. It’s not that they are purposely trying to annoy, instead, they are developing their divergent thinking process. That is, until rational thinkers put an end to their inquisitiveness.

So, don’t just ask why there are waves, or what makes the sky blue. Go deeper. In fact, learn to ask better or more divergent questions such as why did the entire world all agree that blue would be the name for the color blue?

Shimon Peres went on to say, “My greatest regret in life was that my dreams were sometimes too small.”