ALL TOPICS

- Creative Visonary

- Divergent Thinking

- Philosophical Mindset

- ADVENTUROUS SPIRIT

- Imaginative Nature

- Action Oriented

Let's Be Adventurers!

The very first thing I noticed when doing research on the Adventurous Spirit, was how many children’s storybooks foster an adventuresome attitude.

Alice in Wonderland, The Cat in the Hat, The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, Peter Pan, Where the Wild Things Are, Gulliver’s Travels, Percey Jackson and the Lightning Thief, THE BFG, and the ever-popular Harry Potter series are all just a small sampling of the massive collection of storybooks about adventure.

Why do we do this? I began to wonder if all the Disruptors I’ve studied about, the ones with an adventurous nature were read stories as children that sparked their adventurous nature.

I remember when I was younger, reading stories where I found myself imagining I was the hero of the story, venturing on his quest of discovery. Everywhere he or she went, I wanted to go. It sparked my imagination and fueled my desire to do what they did, even if some of it was pure fiction, wands, giants, shires, rabbit holes, hiding away in cargo planes, or finding myself lost at sea on a lifeboat with a large tiger named Richard Parker. Okay, that last book wasn’t until much later, but I still like adventure stories even today. Books like Eat, Pray, Love, Shantaram, Origin, and the Jack Reacher series still get my attention.

Growing up in California, I was gobsmacked the first time I was taken to Yosemite as a young boy. It was shortly after having read the Hobbit, and walking through the forests, seeing the giant sequoias, sleeping under the stars, camping by firelight, I was magically turned into a Hobbit on a quest to save the shire. The only downside was that my mother wouldn’t allow me to go barefoot.

For the past, now coming on sixteen years of research, I wanted to know what drove the Disruptive adventurers that I have written about. I desired to learn about what drives them towards their particular quest, and what they got out of those experiences.

For the purpose of this piece, I specifically looked for adventurers whose journey’s were larger than fiction, but read just the same. I came across one spirited individual who is someone whose accomplishments put many to shame.

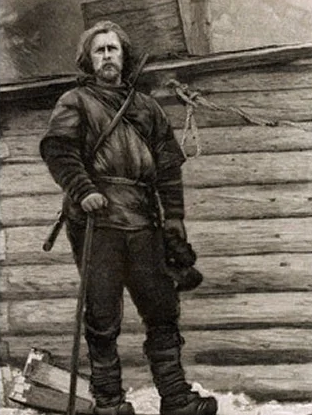

Meet Our Hero

Fridtjof Wedel-Jarlsberg Nansen (10 October 1861 – 13 May 1930), was a Norwegian polymath (that was the first clue as to his adventurous nature), and a Nobel Peace Prize laureate (for his work as Commissioner of refugees for the League of Nations).

How is it that people don’t know more about this amazing guy?

He gained prominence at various points in his life as an explorer, scientist, diplomat and humanitarian. He led a team that made the first crossing of the Greenland interior in 1888, traversing the island on cross-country skis. He won international fame after reaching a record northern latitude of 86°14′ during and expedition on his ship, the Fram from 1893—1896. Although he retired from exploration after his return to Norway, his techniques of polar travel and his innovations in designing equipment and clothing influenced a generation of subsequent Arctic and Antarctic expeditions.

His father was a prosperous lawyer, but it was his strongminded mother, who introduced her children to the outdoor life, encouraging them to develop physical skills. This proved valuable for driving his future. He became expert in skating, tumbling, and swimming, but it was skiing that played a big role in his life. Fridtjof was a tall, supple, and strong man. His physical endurance enabled him to ski fifty miles in a day and the psychological self-reliance his mother instilled within him allowed him to venture on long trips, with a minimum of gear and only his dog for company.

And his deep love for adventure didn’t stop there. At twenty, I was thinking only about education and getting a job, at the same age, he was already excelling in science and drawing and decided to major in zoology. Yearning for adventure, he united his athletic ability, his scientific interests, his craving for adventure, and his talent for what turned out to be nothing short of brilliant achievements that later brought him international fame. But that wasn’t his catalyst.

In 1882 he ventured on a sealer aptly named the Viking to the east coast of Greenland. On this trip he made observations on seals and bears which, years later, he turned into a book; but at the same time, he became entranced by this world of sea and ice. Shortly after, in 1888, he also became the zoological curator at the Bergen Museum, where he successfully defended his dissertation on the central nervous system of certain lower vertebrates for a doctorate at the University of Oslo.

Oh, but it doesn’t stop there for this adventurer

Adventure is Calling

For a long time, Fridtjof had been dreaming up a wild plan to cross Greenland, whose interior, at the time, had never been explored. He decided to cross from the uninhabited east to the inhabited west; knowing that once his party was put ashore, there would be no turning back.

In 1888, A party of six survived temperatures of -45° C, climbed to 9,000 feet above sea level, mastered dangerous ice, exhaustion, and privation to emerge on the west coast early in October of 1888 after a trip of about two months, bringing with them important information about the interior.

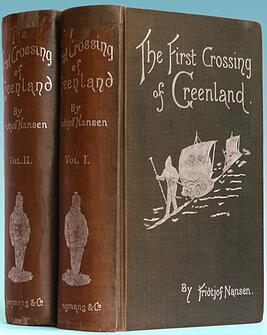

Over the next four years, Fridtjof served as curator of the Zootomical Institute at the University of Oslo, published several articles, two books, The First Crossing of Greenland (1890) and Eskimo Life (1891), and planned a scientific and exploratory foray into the Arctic.

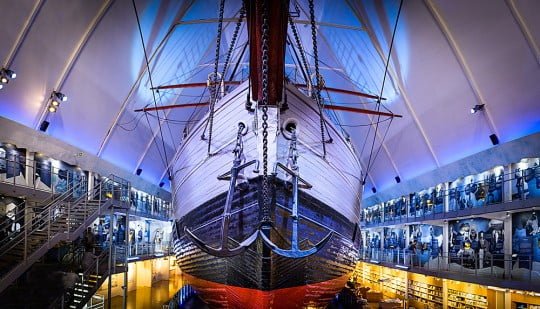

Basing his trek on the revolutionary theory that a current carried the polar ice from east to west, Fridtjof put his ship, the Fram, which was an immensely strong and ingeniously designed ship, into the ice pack off Siberia on September 22, 1893, from which it emerged thirty-five months later on August 13, 1896, into open water near Spitzbergen. But Fridtjof was not onboard.

Photo from the Fram Museum in Oslo

Having realized that his ship would not be able to successfully make the pass over the North Pole, with thirty days’ rations for twenty-eight dogs, three sledges, two kayaks, and a hundred days’ rations for themselves, Fridtjof and a companion, set out in March of 1895 on a 400-mile dash to the Pole.

It took them twenty-three hard days to travel 140 miles across oceans of tumbled ice, getting them closer to the Pole than anyone had previously done. Turning back, they made their way southwest to Franz Josef Land, where they wintered from 1895-1896, before starting south again in May. They successfully reached Vardo, Norway, the same day the Fram reached open water and were happily reunited with the crew on August 21 at Tromsø.

The voyage was a high adventure but it was also a scientific expedition. Now holding a research professorship at the University of Oslo, The Fram served as an oceanographic-meteorological-biological laboratory for him. From that work, Fridtjof published six volumes of scientific observations he made between 1893 and 1896. Continuing to break new boundaries and new ground in oceanic research, he was later appointed professor of oceanography in 1908.

Humanitarian Endeavors

In the spring of 1920, the League of Nations asked Nansen to undertake the task of repatriating the prisoners of war, many of them held in Russia. Moving with his customary boldness and ingenuity, and despite restricted funds, he successfully repatriated 450,000 prisoners in the next year and a half.

Then, in 1921, the Red Cross asked him to take on yet another humanitarian task, that of directing relief for millions of Russians dying in the famine of 1921-1922. Fridtjof accepted the task with an open heart and passionate energy. In the end he gathered and distributed enough supplies to save a staggering number of people, the figures quoted ranging from 7,000,000 to 22,000,000.

And, shortly after, in 1922 at the request of the Greek government, he tried to solve the problem of the Greek refugees who poured into their native land from their homes in Asia Minor after the Greek army had been defeated by the Turks. With a lot of creative ingenuity, he effectively arranged an exchange of about 1,250,000 Greeks living on Turkish soil for about 500,000 Turks living in Greece, with appropriate indemnification and provisions for giving them the opportunity for a new start in life.

Nansen’s fifth great humanitarian effort in 1925, was to save the remnants of the Armenian people from extinction. He drew up a political, industrial, and financial plan for creating a national home for the Armenians in Erivan that foreshadowed what the United Nations Technical Assistance Board and the International Bank of Development and Reconstruction had done in the post-World War II period. The Nansen International Office for Refugees were able to settle some 10,000 in Erivan and 40,000 in Syria and Lebanon.

And the list goes on and on. Sadly, Fridtjof Nansen died of a heart failure in his home at Lysaker, on May 13, 1930.

Two Cambridge University professors of geography wrote: “For scientific achievements and perfection of methods of polar travel, Dr. Nansen takes first place among the explorers of his generation.” The President of the Council of the League of Nations called Nansen “one of the greatest figures in the ten-year history of the League.”

What We Can Learn from Fridtjof Nansen

While not all of us have the physical ability, endurance, perseverance, or determination to live as exceptionally as this man did, we can still gain some great insights into how we too can utilize and develop an adventurous nature of our own.

1: Explorative Desire

Curiosity and wonderment are great drivers for venturing on a quest of the unknown. It’s the igniter that also drove Charles Darwin, Lewis and Clark, Captain Cook, Anthony Bourdain, Amelia Earhart, Rosalind Franklin, Marie Curie, and so many other explorers of their time. This craving to investigate, discover something new, and expand one’s knowledge of information is something we all can learn to tap into. One doesn’t need to be as bold or skilled an adventurer, but it does require the desire to want to learn more, and the curiosity to figure out how, when, and why. What you discover is only equal to how you grow from your experience. Often a journey like this, whether it is discovering something local, or traversing to new countries, or exploring untired landscapes in nature, your personal adventure cannot help but to change and expand who you are.

2: Inquisitive Nature

What are you looking to learn or discover? Why is this important to you? Your catalyst will dictate the why, when, and how you begin your journey. It may be a similar-natured parent who encouraged you to figure things out on your own. It may be an impassioned teacher who showed you a new way to look at the world. It might be the smallest of ideas that got you to see things in a whole new light, sparking a new line or pursuit, as it was for little Albert Einstein, when given a small compass with its magnetic needle.

Be open to observing, reading, and listening from many different sources as are available to you. Do not just rely on the internet to provide you with knowledge and information. Go out and talk to different people. Ask questions. Let them share their stories, ideas, and personal journeys with you. You’ll never know what gems you might discover by broadening your social and networking base. A mother from Teran may have a childhood story that ignites a new thought or idea within you. And you can only get this by stretching your boundaries of comfort. Spark comes from the most random of places at the unlikeliest of times. The real alchemy will require you to be the catalyst, and the only way to accomplish this is to put yourself into the mix.

3: Altruistic Soul

When your nature is one of compassion, caring, and giving, you can’t help but discover new adventures from life and of the soul. When you put aside the self, meaning you take the “you” out of the equation, you start to connect with others and the world around you. This is how you discover new ideas, new thoughts, newer ways to live life. By caring for others, by being attentive to who they are, by becoming interested in things outside of yourself, you gain a whole new outlook on life.

4: Craving for Knowledge

Never stop learning. There is always something magical, mysterious, and adventurous waiting for you to want to discover and know more about. Storytellers are masters at this because they are always looking for new ways to see the world. A new piece of information, a unique, insightful perspective, a funny anecdote, a touching moment of life, these are all gained through the seeking out of knowledge which almost always becomes an adventure. Where do you want to go? What do you want to learn? Who do you want to meet? What burning questions do you have? What drives your spirit to know the answers? Sometimes it’s one small passage in a book that triggers a new thought or idea. The trick to this is not to look at something rationally. A quest for knowledge requires one to be open to seeing things in a different light. For example, I learned this from the Dan Brown book, Origin.

It said, “True or False?” I + XI = X

Then it asks, “Is there is any way this statement could be true?”

What if you turned this statement upside down?

X = IX + I

What knowledge did you just gain? Was this a trick, or did you just learn how to look at things differently? In other words, your ‘perspective’ may be limiting your knowledge.

Other Articles:

Here is a complete list of articles I have written on the Adventurous Spirit. Enjoy!