All disruptions that have impacted our lives for the better are typically selfless pursuits unless, of course, they are for personal gain, and eventually end up hurting or taking advantage of others.

Yes, we all know about the negative disruptions, whose selfish motivations, big egos, and uncaring proclivities ultimately caused others to suffer or be negatively impacted, those selfishly motivated by greed, power, and personal fame, Donald Trump, Adam Neumann (WeWork), Elizabeth Holmes (Theranos), Travis Kalanick (Uber), Anna Delvey (Anna Sorkin), Keith Raniere (NXIVM).

We could also talk about the most egregious ones throughout history like Mao Zedong, Joseph Stalin, Adolf Hitler, Pol Pot, Francisco Franco, Leopold the II, Kim Il-Sung, Saddam Hussein, Idi Amin, Mengistu Haile Mariam, Josef Mengele, and many others.

But real Disruptors, those who change the world for the better, are often unknown or lesser known. Their motivations were not the desire to become a celebrity, and there are cases where their disruptive ideas never brought them wealth, even when their ideas benefited mankind.

Disruption is not always an invention. Sometimes disruption is a selfless act, unknown at the time, but one that ultimately impacts the lives of many in the most positive ways.

In a past article, I mentioned Shimon Peres, the ninth President of Israel (https://craigcopeland.blog/philosophical-mindset/the-philosophy-behind-dreaming/).

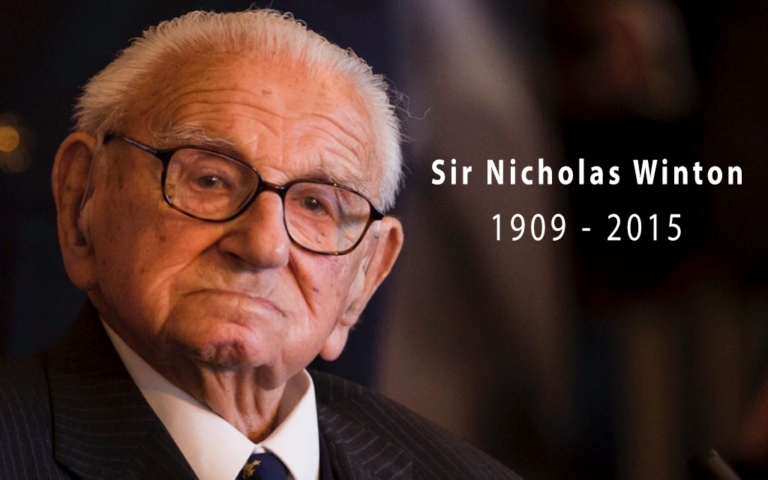

Today, I want to talk about Nicholas Winton, a name you probably never heard before.

Nicholas George Wertheim was born in London, England, on May 19, 1909. He was the oldest of three children whose parents, Rudolf and Barbara Wertheimer, were German Jews who later converted to Christianity and changed their last name to Winton.

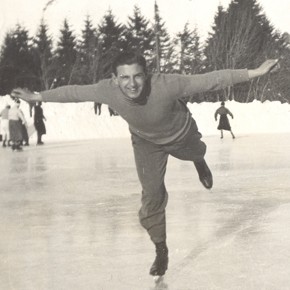

Nicholas grew up with considerable means. His father was a successful banker who housed his family in a 20-room mansion in West Hampstead, London. After attending Stowe School in Buckingham, Winton followed in his father’s footsteps and apprenticed in international banking. Afterward, he worked in banks in London, Berlin and Paris. In 1931 he returned to England and began his career as a stockbroker.

In December 1938, for whatever reason, Winton decided to skip a planned Swiss ski vacation, and instead visit a friend who was working in the western area of Czechoslovakia known as the Sudetenland,

It turns out, his friend was involved with helping refugees in Czechoslovakia which had now fallen under German control.

It was during this visit that this self-made, successful stockbroker witnessed firsthand the dire situation of the country’s refugee camps, which were overfilled with Jewish families and other political prisoners.

Winton became aware of the efforts already in place to organize a mass evacuation of Jewish children from Austria and Germany to England, and he wanted to replicate a similar rescue effort in Czechoslovakia.

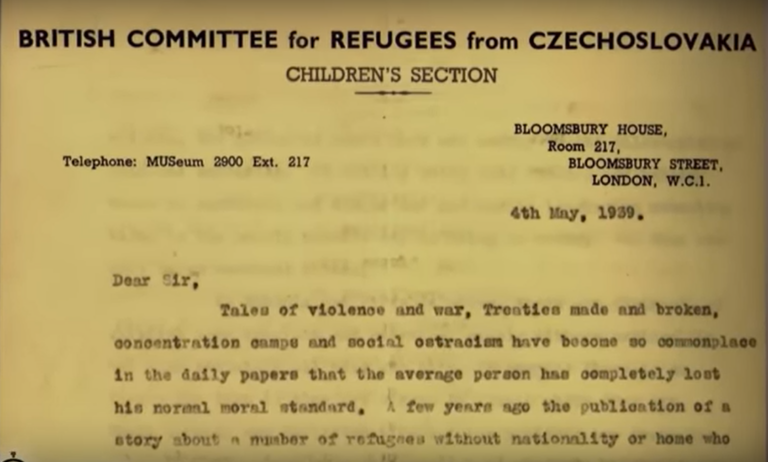

Working initially without the group’s authorization, he set up shop to begin his clandestine task of figuring out how to get children out of German-occupied Czechoslovakia. He used the name of the British Committee for Refugees, falsely added the subtitle “Children’s Section”

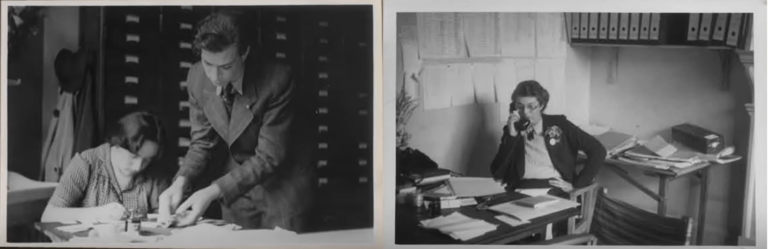

and, with the help of his mother and volunteers, began taking applications from Czech parents at a Prague hotel. Thousands soon lined up outside his office.

The Children’s Section operated from a tiny office set up in central London. His mother was in charge. The staff were all volunteers. This unassuming stockbroker did his job by day and wrestled with the British bureaucracy in the evenings.

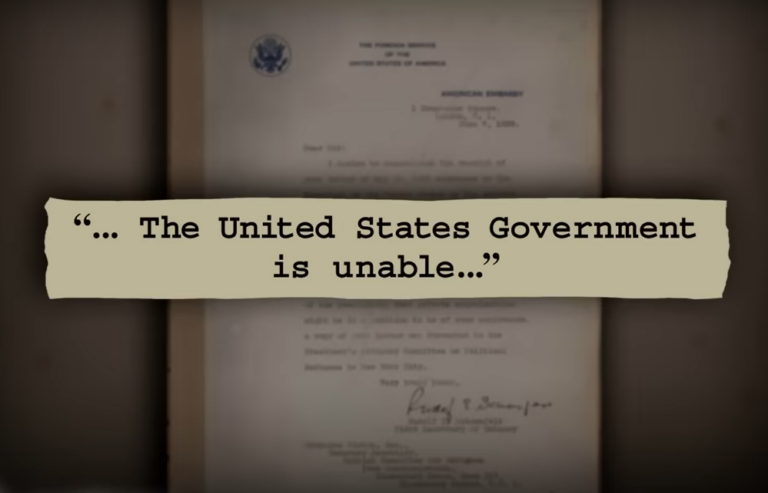

He contacted the Americans but they wouldn’t participate, which Winton said was a pity, because they could have gotten hundreds more children out.

Winton moved quickly to get as many children out of German territories as possible. While, unfortunately, one train of hundreds of children was stopped by German soldiers, Nicholas and his team were able to get 669 children safely out of Europe and into England. Winton believed that ‘none of the 250 children on board was heard of again’, which was an awful feeling for him.

Some of those children he did manage to rescue went on to perform their own noble deeds:

- Leslie Baruch Brent (1925–2019), became an immunologist who did groundbreaking work on immune tolerance

- Alf Dubs, Baron Dubs (born 1932), went on to become a British Labor Party politician and former Member of Parliament

- Heini Halberstam (1926–2014), became a mathematician

- Renata Laxova (1931–2020), became a pediatric geneticist

- Isi Metzstein (1928–2012), grew to become a modernist architect

- Gerda Mayer (1927–2021), wrote poetry

- Karel Reisz (1926–2002), became a filmmaker

- Joe Schlesinger (1928–2019), moved to Canada and became a Canadian television journalist and author

- Yitzchok Tuvia Weiss (1926–2022), became Chief Rabbi of the Edah HaChareidis in Jerusalem

- Vera Gissing (1928–2022), became a writer and translator

Nicholas never sought accolades, and never disclosed publicly what he had done. But his deeds did not go unnoticed. Many years later, at the age of 94 Nicholas Winton was knighted by Queen Elizabeth II for services to humanity.

Sir Nicholas died in July 2015, aged 106. In an interview touting his heroic deeds, Nicholas once said, “Why are you making such a big deal out of it? I just helped a little; I was in the right place at the right time.”

He continued his tradition of ‘being in the right place at the right time’… for the next fifty years of his life, Winton volunteered to form a local society of Abbeyfield, the national charity that provides support helping mentally handicapped people and building homes for the elderly.

Wow.